Pre-order ‘Long Road to Nowhere: The Lost Years of Richard Trevithick (Part One)’ now, HERE.

As much as he was cursed with bad timing, Richard Trevithick also liked to make his own life as difficult as possible with a mix of defiance and belligerence. It appears that Don Ricardo was itching to escape from the clutches of Camborne almost as soon as his steam engines left for Lima in 1813. As he waved goodbye to the ship, and to Francisco Uville, the man who had happened upon one of his engines in London in the first place, he couldn’t help but feel he should be aboard too. This brave man who could not stand to be at sea was already seasick as the ship left the dock; yet he had made the journey to and from Lima at least 3 times already and now for the final time, he was leaving England with Trevithick’s finest work.

From that moment he began scrambling around – whether his wife knew or not is unclear – for a ship that would take him on the arduous journey around Cape Horn and all the way to Lima. The only boats that went that far were whaling ships and he was, for the time being, out of luck.

None of the South Sea whalers will engage to take me to Lima, as they say they may touch at Lima or they may not. Unless I give them an immense sum they will not engage to drop me there.

Unsent letter dated 9th December 1815 (from ‘The Life of Richard Trevithick’, 1872)

It would appear that something changed inside Trevithick’s mind around this time. From 1813 until his death in 1833, letters seemed to dry up and words written by the man himself became increasingly rare. When he eventually reached Lima in 1817 after a 4-month journey, he sent a handful of letters home upon arrival and then after that…nothing.

His restless legs could not settle and this letter, dated 9th December 1815, shows his frustration. The wind rolling in across the Atlantic was whispering his name. Come forth, come forth and seek riches far beyond the confines of Cornwall.

After failing to find a ship to Lima and completely devoid of patience, he began to hatch a plan that was, even by his own high standards, completely deranged.

I hope to leave Cornwall for Lima about the end of this month, and go by way of Buenos Ayres, and cross over the continent of South America, because I cannot get any other passage. To make a certainty I shall take the first ship…preparations for which I have already made.

Unsent letter dated 9th December 1815

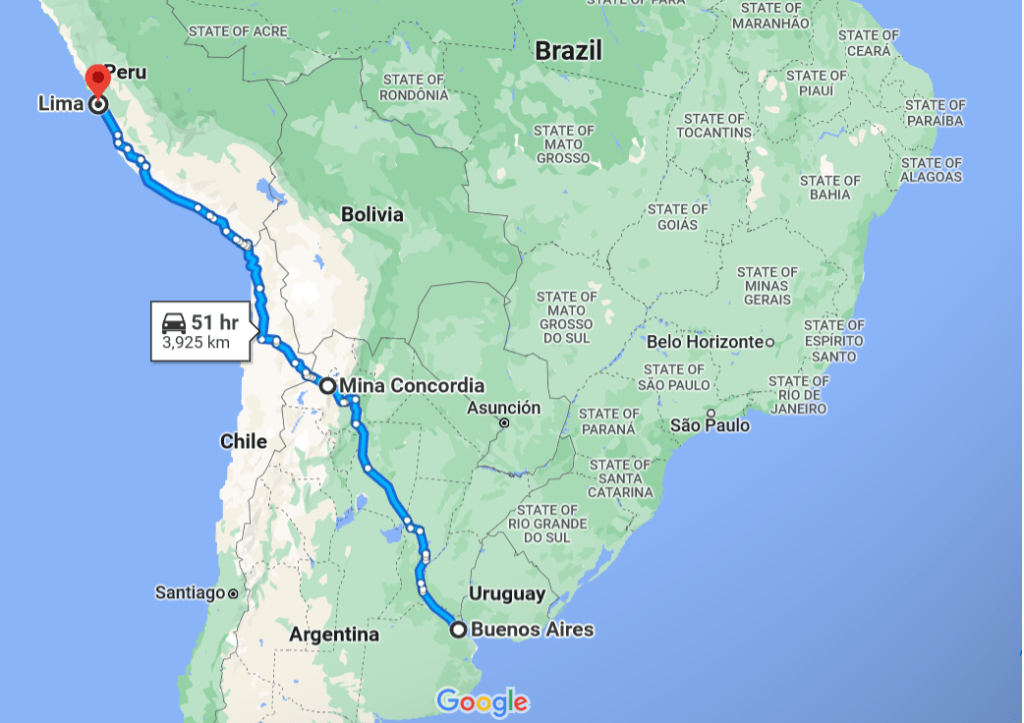

Never one for the easy route (through life, as well as transport) he had decided that rather than sit and wait for a ship all the way, a better idea was to land at Buenos Aires on the Atlantic coast and attempt his first ever expedition, crossing the entire continent. Heading north west towards Salta via Rosario and Tucuman, then crossing over the Andes mountains into modern day Chile and then winding north into Peru and finally Lima. Today, the shortest way to make this journey is just under 4000 kilometres, well over 4000km if you take the Pan-America Highway via Mendoza and head through the Andes via the Uspallata Pass.

It begs the question: had he bothered to consult a map? Was he aware of the scale of this journey? Even for a man as fearless and perhaps naïve as Trevithick this was ridiculous. On muleback this trek would take 3 months at least; provided the mule didn’t drop dead from exhaustion or throw its rider down the side of a narrow ravine, never to be seen again. Something also tells me that Trevithick would refuse to hire a guide and insist he could make the journey himself.

The voyage that was

Some 85 years later, in 1899, another Cornishman and native of Camborne by the name of W.R Bateson undertook some of this journey by train from Buenos Aires, north-west past Rosario, San Miguel de Tucuman and Salta and thence to Mina Concordia on muleback. He described his destination as

‘the most lonely place possible, 120 miles from a town.’

W.R Bateson, letter dated 20th October 1899 (Camborne School of Mines Magazine, December 1899)

Coincidentally, Mina Concordia is along the route that Trevithick would have taken towards Lima, although Bateson’s final destination was a mere 1600km from Buenos Aires, barely halfway to Lima and still a difficult journey 66 years after Trevithick’s death.

And we must remember that Bateson had the luxury of Trevithick’s greatest legacy to make his journey much quicker; trains were still in their infancy when Trevithick wished to attempt this. For Bateson, it took almost 48 hours by train over four or five days just to reach Salta and from there it was still 120 miles or 3 days on muleback to reach the mine. (Bateson’s journey is worthy of it’s own article; the letter he sent home describes his travels through Brazil, Uruguay and Argentina in vivid detail and you’ll see that dreckly my friends)

Some quick sums that are simple to everyone but me would work out how long it would take for Trevithick to reach Lima solely by animal transport. Bateson averaged 40 miles a day but I don’t think a mule nor Trevithick’s backside could handle doing this every day. There would need to be some days of rest otherwise the journey would quickly become a race to see who could die first: man or animal. 40 miles a day / 2400 miles (ish) to Lima. 60 days of non-stop riding, but that doesn’t sound feasible nor remotely tolerable.

With the benefit of hindsight, it is probably wise Trevithick didn’t undertake this mission, but one does wonder what scuppered his plans, ones allegedly he had already made in the letter. Despite his insistence, the letter was never sent and he waited another year for a boat all the way to Lima for his grand adventure to begin.

A new adventure to recreate

Before I left for Chile I was certain I had read Francis Trevithick’s biography inside out and missed nothing of the details pertaining to South America. I was sadly mistaken. But nevertheless, upon learning of this, I immediately became gripped by the same fever that must’ve overcame Trevithick: a mix of restless excitement, delusion and naivety.

My own journey, while mildly impressive (depending on what form of transport I use) would be incomparable to the theoretical journey of Trevithick and the actual journey of Bateson and I will not be able to shake the idea of recreating it entirely from my mind. This is partly because I have recently discovered Ed March and his YouTube channel ‘C90 Adventures’ that detail one fearless man’s trips around the world on a clapped out Honda motorbike. He has inspired me to undertake some more silly ideas to make this project even better: recreating trips that never were, like Buenos Aires to Lima or fictional missions like trying to sail from Guayaquil to Bogota, even though Colombia’s capital city is nowhere near the coast. What’s the worst that could happen?

This will inevitably become one of many detours I plan to take while on the Trevithick Trail (not the first, I’ve already taken a detour 12 hours south of Santiago to a small town called Pucón to climb a volcano) an idea that widens in scope almost every day. But how will I do it? A series of trains would be the most symbolic, but also the most tedious, involving little more than me staring vacantly out the window.

Fear not. There is no rush. More on this in good time…

If you liked this article please like and share it. If you never want to miss a post you can subscribe and get an email every time I upload. Cheers n gone once more.

Leave a comment