Pre-order ‘Long Road to Nowhere: The Lost Years of Richard Trevithick (Part One)’ now, HERE.

During my trip so far I’ve visited abandoned train stations, hiked along both active and disused railways and even been woken up by them rumbling through Antofagasta in the middle of the night, but so far on the trail of Richard Trevithick, the man who invented the steam locomotive, I have seen the sum total of one train. As I waited on the other side of the Chilean-Bolivian border for the driver to have breakfast (he ushered me into the shack and encouraged me to eat but the vast array of tumour soups didn’t look appealing just yet) I finally saw one passing into the tiny Chilean town of Ollague. No longer the romantic trains of old, it was a filthy (in every sense) diesel locomotive pulling 8 or 9 empty orange carts.

Once the forefront of technology, all that remains of the first machines to conquer desolate places like the Atacama desert and the Altiplano are old relics and rusting railroads. While the railroad didn’t make these places any more hospitable, for the first time they became navigable. Suddenly goods and passengers could pass through these empty places in speed and even style (if you had the money). The world became a lot smaller, a lot more accessible all thanks to Trevithick and others after him but following the invention of the motorcar, the train became old news in the hyperactive world of scientific progress.

In Bleakest Bolivia

Uyuni is one of the best places to see this decline first hand. It was once an important hub that connected trains from all points of the compass; La Paz and Oruro from the north, Argentina and Tupiza from the south, the massive mines of Potosi and Pulacayo from the east and the port of Antofagasta from the West. Towards the end of the 19th century there were plans to expand the network even more, but when the mines ran dry, no longer was there much point. The timetable got smaller and smaller and when the silver ran out, the trains that were sent to Uyuni for repair never left; stripped of their engines and then dumped at the edge of the town where the ‘Train Cemetery’ now resides. Uyuni is an incredibly bleak town and the train graveyard is the single attraction within it. The fact anyone anywhere has even heard of Uyuni is purely because it is the last sizable chunk of civilisation before the immense sparsity of the Salt Flats, one of the biggest tourist attractions in South America.

This is perhaps the only thing that keeps Uyuni afloat nowadays: tourism. Sound familiar? Cornwall and Uyuni certainly share some characteristics; once industrially important but now irrelevant and both can seem incredibly bleak and desolate places, only Uyuni looks like this all year round. You cannot move for tour agencies and hawkers all offering the exact same thing – different length tours of the Salt Flats at competing prices with varying levels of luxury and comfort thrown in for good measure.

But I wasn’t here for that just yet. I must be the first person to arrive in Uyuni and leave again without having done a tour. I had more important things to do: trainspotting. I left my bargain basement hotel disappointed. All the reviews said the rooms were decrepit, with blood and dirt and shit up the walls and filthy beds with unwashed sheets. I was disappointed to find none of this was true – it would have been a good introduction to Bolivia otherwise.

The Trainspotter Returns

Before I wandered to the edge of the town to look at the train graveyard, I went first to the Museo de Ferrocarril. The grand pillars, whitewashed walls and marble steps did not fit in with the rest of the town’s aesthetic: choking dust, rubbish strewn in every place a pavement should be, and all flanked by derelict or collapsing buildings. So many buildings in Bolivia look both abandoned or half-built and it’s nigh on impossible to tell which is true.

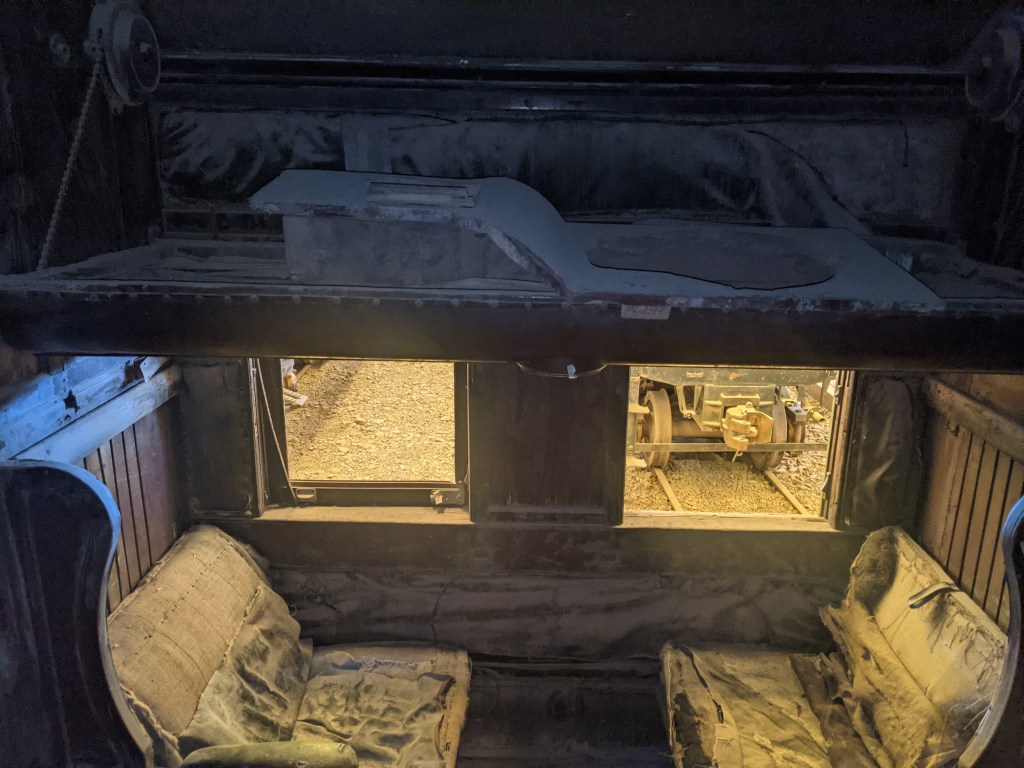

I walked into the cavernous building wandering how often they had to repaint those glistening white walls, paid 5 bolivianos for entry and signed my name in the guestbook. It was late in the day yet I was only the third visitor and the youngest by far. The bored-looking man ushered me into the museum itself, which must have once been the central station or the engine shed in Uyuni’s heyday (heyday was something I struggled to imagine). To my right stood an immense row of old locomotives and to the left and collection of passenger carriages. I immediately jumped off the walkway and on to the gravel below. Dwarfed by these old steam engines that lay dormant, I couldn’t help be impressed. These are hefty bits of kit, far larger than the ones I saw in Copiapó. It was almost a struggle to clamber up into cabin, even for someone tall like me. I couldn’t imagine one of the tiny races of Bolivian men doing the same.

The accolade of trainspotter becomes more apparent to me with each passing day. Not in an autistic, scheduled and collector-ish way but simply to marvel at the size of these machines. As I jumped up and down from the locomotives I was baffled. When you eventually see a modern and slick train arriving 2 hours late at any train station in Britain, it never seems that big, not least because you’re stood on the platform. It really feels like every 20th century engineer is overcompensating for something – these old machines are just enormous.

The passenger carriages were as dusty as the roads outside but even in this state they spoke of the lost age of railroad romance – for those that could pay for it of course. One thing was abundantly clear, for the average passenger trains have dramatically improved. No longer is the basic carriage akin to a cattle shed, with four rows of benches placed lengthways in the carriage and any sudden movement shoving travellers onto the floor in a heap.

Leaving the museum and the Hogwarts sleeper cars behind, I walked to the edge of town slightly wary of the attitude. I was now at over 3600m (11,800ft) and I’d spent most of my life at sea level. Ascending the stairs to my room in the hotel left me delirious. Mild breathlessness aside it was fine but it was my biggest worry. I thought the edge of town might be dangerous but it was just bleak.

Cementerio de Trenes

The train graveyard was perhaps the most bleak sight I’ve ever laid eyes upon, yet somehow infinitely more attractive than the town itself. Thankfully when I arrived the sun was slowly setting over the Martian mountains in the distance and tourists were few and far between. Every single tour that leaves Uyuni starts or finishes here and the place is overrun with people doing nothing but taking photos of each other, of themselves or flying drones overhead for their subscriber-less YouTube channel. Just like in the museum, I was a little kid again. I climbed up them; I hauled myself on top of them and ran across, I slid down the rusting metalwork and made my trousers dirty; I skirted along the edge like I was in an old Western or a James Bond film. I took a few photos of this post-apocalytpic scene on the edge of town, but for the most part, I did what tourists forget to do these days: experience the place they’re in.

A few stragglers appeared and did exactly that. They took photos, they walked around looking at their photos and then took more photos. I haven’t seen much of the world yet, but every wondrous place, every marvellous building or landscape is simply filled with people staring at it through their camera. You would almost feel weird for daring to buy a ticket and enter any place on earth just to stumble about in awe of your surroundings without taking any photos. Even taking one or two photos seems insufficient now. The next stop is watching someone else’s VR footage of a location whilst you drool and defecate in your Wall-E style floating armchair.

I returned to this, the bleakest of towns a few weeks later to do a tour of the Salt Flats and the first stop was this place, only now it was absolutely rammed with people taking photos. My friends and I stood on top of one of the locomotives talking shit about tourists and about how seemingly 95% of the population are incapable of simply appreciating any location without a phone in hand.

As I stood between the arrow straight tracks once more, looking off into the distance, all I could dream of was train hopping through the desert. My daydream was shattered by an angry German couple demanding me to move so they could take photos of each other on the tracks. Oh to be a tourist…

Leave a comment