Pre-order ‘Long Road to Nowhere: The Lost Years of Richard Trevithick (Part One)’ now, HERE.

Antofagasta is a city and a region that owes itself to the nitrate trade that exploded during the 19th century. From the surrounding desert, the goods were transported back to the port via railroad and from there, shipped across the world. Once a Bolivian territory known as the Litoral, it was taken by the Chileans during the War of the Pacific and the region of Antofagasta is the second most northern province of this strangely shaped country.

It is still very much an industrial city to this day, far off the tourist trail and even more so off the backpacker trail, making my presence slightly peculiar as always. Only the high-rise apartment blocks would have seemed alien to Cornishman George Hicks, who worked for the ‘Compania de Salitres y Ferrocarriles de Antofagasta (CSFA)’ in the mid to late 19th century as profits soared and war loomed on the horizon, of which Hicks would play a very interesting part…

Arrival into Antofagasta

Almost from the get go, I thought my time in Antofagasta was to be a disaster. There were two hotels bearing the same name, neither of which resembled the one I had booked but luckily they were both within a few minutes’ walk of each other.

When I arrived at the nearest one, I knew that it wasn’t the right place. Still, I got in the lift up to the sixth floor regardless, because I like to humiliate myself at least once a day no matter what. When I was buzzed in I walked past a string of rooms for meetings and one giant conference hall. This was definitely the wrong place. I knew this for certain, yet for some reason I still walked up to the front desk and claimed I had a reservation. The woman behind the screen looked up at me suspiciously. I was incredibly sweaty, my backpack slung over my left shoulder. I was certainly not the usual clientele of such a place.

‘Are you sure?’ she asked.

‘No,’ I replied confidently, ‘but I can’t find the actual hotel,’

‘Can you show me your booking please?’

I slid my phone across the counter.

She nodded, ‘this is not the right place.’

I knew that already, I just love making myself look a fool. I had been looking forward to it all day.

‘There are two hotels with the same name no?’ I inquired.

‘Three,’ she replied flatly.

I slammed my head on the countertop unnecessarily hard. There is no method to this madness.

She took pity upon this foolish gringo, writing down the actual address on a slip of paper and handing it to me.

‘Thank you, and forgive me. I am stupid,’ I declared as I headed for the lift once more.

She smiled sympathetically. Note that she didn’t disagree with me

So, there are in fact three hotels by the same name, all within walking distance of each other, all completely unaffiliated. The third and presumably cheapest was the one I needed but it did not exist on any map, hence my confusion. When I finally rocked up at the right place, the three ladies sat by reception seemed surprised by this information. They probably assumed I’m an idiot, and they are certainly correct.

Did George Hicks accidentally start a war?

I’d come here in search of another equally belligerent Cornishman, George Hicks. Not quite as deranged or as interesting as Trevithick, but possessing similar flashes of that fiercely independent spirit that most Cornish migrants took with them wherever in the world they went. He arrived to Antofagasta when it was part of Bolivia to work within the nitrate industry, specifically the CSFA, as general manager of the company.

What caught my eye about Hicks was not his contribution to the Chilean nitrate industry (I have absolutely no idea what nitrates are even after visiting the museum dedicated to the trade – more on that later) but rather that he inadvertently started the War of the Pacific, fought between Peru, Chile and Bolivia between 1879 and 1883. He was not solely responsible for the war of course, the true reasons, money and mining, had been bubbling away nicely for decades as the nitrate industry got increasingly lucrative and the territorial claims to the rich Atacama desert got ever more hostile.

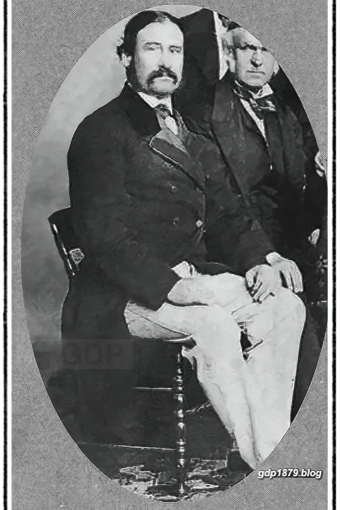

Instead, his defiance was one of the last acts before out and out war broke out, so you could say this chubby, moustachioed Cornishman’s behaviour was the final straw.

On the 11th January 1879, the Bolivian government issued a warrant for Hicks’ arrest over unpaid debts incurred from a retrospective tax introduced by the Severino Zapata, Governor of the Litoral (what Bolivia called the Atacama region). Assets of the company were to be seized and sold at public auction on the 14th February. Rather than submit to the Bolivians whim, Hicks made contact with the Chileans.

He made it clear in letters that he despised the Bolivians, describing them as a ‘bunch of savages’ and a ‘plague’ that the Chileans needed to sort out. He definitely joined the right side, for Chile gained the most from this war. They took the entire region of Antofagasta from Bolivia and the northernmost province, Tarapaca, from the Peruvians and in turn left Bolivia a landlocked country. The greed of Severino Zapata was to blame for this, and perhaps Bolivia is one of the poorest countries in South America because of his actions prior to the war and the losses incurred during it.

Now Chile controlled the territory from Antofagasta all the way up to Arica by the new Peruvian border, way over 700 kilometres of new land, all rich in nitrates and other minerals. The boundaries have stayed basically the same ever since, a nice addition to the already strange shape of Chile, extremely long but incredibly thin.

The Chilean navy had been eyeing up the port of Antofagasta for some time and four days prior to the warrant a warship, Blanco Encalada, arrived and had been lurking in the bay. Hicks did not speak kindly of the Bolivians and the Chileans welcomed him with open arms, allowing him to flee to the safety of the warship.

On the day of the planned auction, the Chilean navy occupied Antofagasta with little or no resistance; just 200 men were required to take the town as most of the residents were already Chilean. Hicks was now being sheltered by the Chilean consul Salvador Reyes and with the manager of the largest nitrate company on their side, Chile had the upper hand. War was declared on the 1st March 1879 and Chilean naval and land campaigns overran the forces of both Bolivia and Peru within two years.

It seemed inevitable that war was going to break out, but Hick’s actions were one of the last things to happen before out and out war was declared. It would not be amiss to say that he played a role in the end of peace and the arrival of war. Chile needed new economic possibilities and the nitrate industry was immensely profitable, so war was unavoidable, but just imagine this man, described by the locals as tall and fat with an enormous nose; the hardened bachelor always impeccably dressed; irascible by nature, starting a war in a country so far from his homeland.

He certainly shared some traits with Trevithick – defiance, belligerence and a fiercely independent spirit but the similarities end rather quickly and while Hicks was an interesting man, I mention him here by way of contrast. Like most other notable (Cornish) figures who ventured to South America to work in the mining industry, Hicks returned home comfortably rich, perhaps even a millionaire by today’s standards. He built himself a mansion in Newquay and lived out the rest of his days in comfort.

Others like Robert Harvey, further north in Iquique and John Penberthy in Bolivia (more soon) ended their lives in the same fashion, handsomely rich. Whereas Trevithick, far smarter, industrious and yet completely lacking in patience, suffered the exact opposite fate. One of the most ingenious and overlooked inventors of all time died penniless because the money he was offered, the money he could have used to build himself a comfortable retirement home was rejected or squandered for endlessly ridiculous reasons. The first to forge this trail and the only one to fail in his assignment.

Arrival into Antofagasta…continued

The Antofagasta I had arrived into seemed different to everywhere else I had visited in Chile prior. I met Nelson, a local photographer who told me that there are large communities of Colombians and Venezuelans in the city. That influence is immediately obvious. Instead of reggaeton being blasted from every shopfront, it was now more likely to be salsa or meringue. This sizable minority gave the city a more ostentatious, almost Caribbean feel that is a stark contrast to the slightly more subdued nature of the Chile I had visited previously.

I arrived at the worst possible time for research, in-keeping with my disastrous timing everywhere else. Everything in Copiapo was closed when I passed through and now here in Antofagasta all the museums and libraries had shut down for the weekend. By the time I’d met Nelson in Plaza Colon it was just after 5pm and while he gave me a brief tour of the surrounding area, pointing out two or three museums I should visit when they reopened next week, the doors were shut and locked right before our eyes.

‘You chose the worst time to arrive,’ he laughed.

At least I’m consistent…

We took a bus to ‘Las Ruinas de Huanchaca’ at the southern end of the city. The imperious red stone remains of a silver foundry overlooked the sleek, modern museum built in its shadow. Obviously, that was shut too. We arrived at the gate and a curiously placed guard told us the museum shut at 18:00. Nelson took out his phone, chuckled again and showed me the time: 18:01.

Some kind of private function was taking place in the grounds, hence the security guard, so we couldn’t even enter to look at the ruins as hoards of locals dressed in evening wear shuffled in past us.

“Come back tomorrow,” he told me as we turned around and walked back into the city.

I was starving. My diet had been atrocious over the past week or so and it was not going to get any better whilst in Antofagasta. We went to the central market to eat and I was surprised to find the menu of the day was only 5,000 pesos (about £5). So there were cheap places to eat in Chile, I thought, as long as you had a local on your side who knew where to look. It was nothing special, but it was hearty and great value for money. I ordered a Limon Soda and Nelson burst out laughing.

‘What’s so funny?’ I demanded.

‘You don’t have this in England?’ he asked.

‘No,’ I replied.

He looked shocked and surprised but kept chuckling about it every time I took a sip. It was a lie of me to say we don’t have Limon Soda, it tastes just like Lemon Fanta, but when in Chile…

For the next four days, this was to become a running joke between us. I still have no idea why.

Part 2 coming soon…if you enjoyed another dose of my failings please like, comment, share and follow the blog so you never miss another post.

Leave a reply to Joel Griffett Cancel reply